The Artist

Tyeb Mehta was one of India’s most influential modern artists, whose work powerfully shaped the language of post-Independence Indian art. Born in Kapadvanj, Gujarat, and raised on Mohamed Ali Road in Bombay, Mehta grew up within a dense urban milieu marked by cultural coexistence and, later, the trauma of communal violence—an experience that left a lasting imprint on his artistic vision.

Initially drawn to cinema, Mehta studied cinematography briefly and worked at Famous Cine Laboratories in the mid-1940s before turning decisively toward fine art. His years at the Sir JJ School of Art (1947–1952) brought him into contact with members of the Progressive Artists’ Group, situating him within the forefront of Indian modernism. His first solo exhibition in 1959 marked the beginning of a steadily rising international reputation.

The 1960s were formative: living in London exposed Mehta to European modernism and the avant-garde, while later encounters with American Minimalism helped him break through a creative impasse. In 1969, an accidental slashing of black paint across a canvas revealed the diagonal—a compositional device that would dominate his work for a decade and become a defining feature of his visual language. His only film as director, Koodal (1970), extended his exploration of fractured, traumatised forms and earned critical acclaim.

A residency at Santiniketan in the 1980s marked another major transformation. Immersed in rural life and indigenous ritual, Mehta produced some of his most celebrated works, including Santiniketan Triptych (1986–87). In later decades, his imagery—from Kali and Mahisasura to falling figures and trussed bulls—evolved toward a more redemptive and contemplative energy, culminating in works such as Celebration (1995).

Honoured with numerous awards, including the Kalidas Samman, Padma Bhushan (2007), and major recognitions from Lalit Kala Akademi and the Government of Maharashtra, Tyeb Mehta remains a towering figure whose art confronts violence, suffering, and transcendence with austere clarity and enduring power.

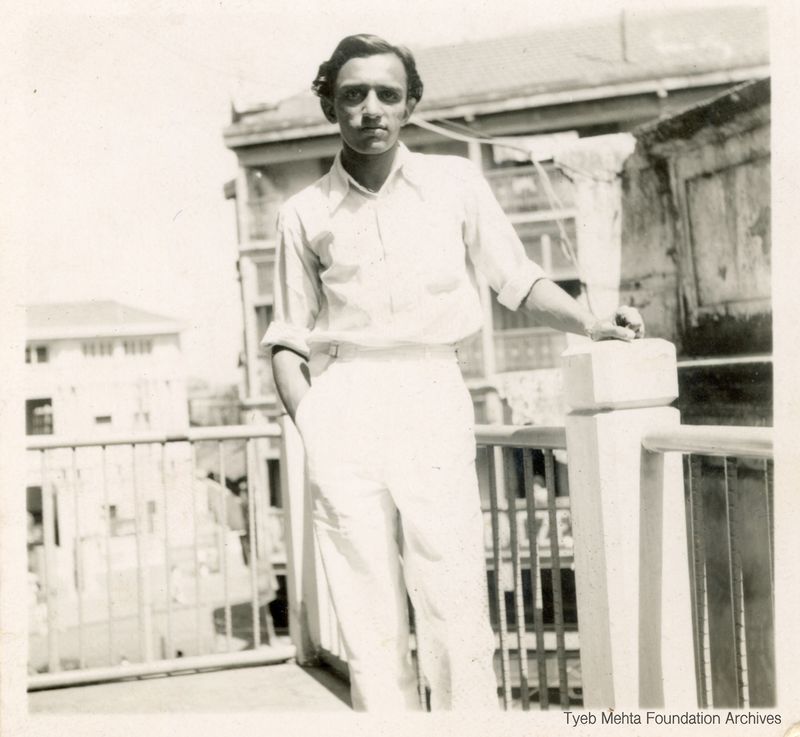

Young Tyeb Mehta, c. 1940s

A full length shot of Tyeb Mehta, dressed in a shirt and trousers, standing on a terrace, his hands resting on a pillar.

Tyeb Mehta is born on 26 July in the Dawoodi Bohra community at Kapadvanj, Gujarat.

Tyeb is educated in Bombay and lives at Mohammed Ali road. Growing up, he dabbles in film poster painting due to his family business in cinema. In addition, he watches Hindi and Hollywood movies.

I was born into a sort of liberated ghetto… the Bohras had been assured of their religious freedoms under the British. They never participated wholeheartedly in the Independence movement. At the age of twenty-one, I was living in a void. I had practically no contact with the outside world. Years later in London, working in the most menial of jobs, I was still trying to break out of those shackles, to emancipate myself. Independence for me was personal as well as national… I wanted to identify with the new nation as a whole rather than remain bound to the community.

— Interviews / Speeches, In Conversation with Nikki Ty-Tomkins Seth, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

In 1944, Tyeb studies Cinematography at Fazalbhoy Institute, St Xavier’s College, Mumbai. Disappointed by the excessive theory over practice, he leaves the course.

He joins Famous Cine Laboratory, Tardeo, where he assists a film editor for two and a half years from 1945 to 1947.

There were elements of violence in my childhood. The generation before mine had developed a certain aggressiveness as they gradually moved out of the community to make their fortunes and I remember that violent street fights were easily triggered off in the neighbourhood. One incident left a deep impression on me. At the time of partition, I was living on Mohamed Ali Road, which was virtually a Muslim ghetto. I remember watching a young man being slaughtered in the street below my window. The crowd beat him to death, smashed his head with stones. I was sick with fever for days afterwards and the image still haunts me today. I am paralyzed by the sight of blood. Violence of any kind, even shouting…

— Interviews / Speeches, In Conversation with Nikki Ty-Tomkins Seth, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

India

The 1930s were politically charged with street protests, like the Non-cooperation and Civil Disobedience Movement, displaying a sheer rise of Indian nationalism and Gandhian ethos — all influencing artistic thought. The partition generated India-wide communal protests, wherein Bombay was impacted by the infamous riot, deepening the rift between Hindu and Muslim zones–forbidding free movement in several south Bombay locals.

Due to World War II in the 1940s, Bombay art scene also noted the entry of the triumvirate: Emmanuel Schlesinger, Rudolf von Leyden and Walter Langhammer. They not only served as patrons to the Progressives and their batchmates in JJ, but also widely exposed them to European modernism–which will eventually kindle their aspiration to experience it first hand.

In the 1950s and 60s, several modern Indian artists, including, for example, S.H. Raza and Akbar Padamsee, among others, moved to Europe—Raza to Paris in 1950 after a scholarship from the French Government, and Padamsee to Paris in 1951. London and Paris were major centers for abstraction and modernism before shifting its reigns to America. Following this wider migration, Tyeb Mehta also travelled to London.

Global

With the rising power of Nazism, the globe witnessed a massive migration within Europe and later to the US. The Nazi regime (under Hitler) branded all modern art as “degenerate art” (Entartete Kunst) and banned artists associated with Expressionism, Dada, Bauhaus, and Surrealism. Artists like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy migrated to Germany. Due to this tumult, several known-for-art cities like Paris, etc. were hampered, which later revived.

The U.S. emerged as the new global centre of modern art after the war. The influx of European émigrés like Mondrian, Duchamp, Breton, Kandinsky, etc. shifted avant-garde activity from Paris to New York. The trauma and disillusionment of war helped catalyze Abstract Expressionism, with artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman seeking new, universal forms of expression — large, gestural, emotional, spiritual.

The 1960s were one of the most dynamic decades in global art — marked by experimentation, rebellion, new media, and a shift from modernism’s seriousness to postmodern play. Art moved out of the gallery, into the street, into politics, and into life itself. Artists reacted against the solemnity of Abstract Expressionism (dominant in the 1950s) and embraced irony, consumer culture, and conceptual ideas.

Tyeb joins Sir JJ School of Art with the help of Mr AA Majid, ex-jjite and a noted art director, whom he bumps into while travelling in a tram car.

In 1950, Tyeb visits Delhi to see the exhibition Indian Art at Rashtrapati Bhavan, which inspires him to explore Indian aesthetics.

In 1951, Tyeb marries Sakina Kagalwala.

From 1947 to 1952, Tyeb’s charged years at JJ School introduce him to the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) members, which included Akbar Padamsee, Vasudeo Gaitonde, KH Ara, MF Hussain, and SH Raza, among others —the friendships with whom were etched for a lifetime. Moreover, the atmosphere marked by various disciplines like poetry, theatre, arts and traditions inspires him immensely and paves a unique way for his expressions.

His teacher Shankar Palshikar, notably, had a great influence over Tyeb’s modern art sensibility.

Tyeb Mehta with Bal Chhabda and Ram Kumar, c.1960s

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta standing together with Bal Chhabda and Ram Kumar. Inscribed with names of the three artists and ‘For Mr. Mehta’ on the reverse.

Tyeb Mehta with Krishen Khanna, c. 1960s – 1970s

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta with Krishen Khanna at an exhibition.

Tyeb and Sakina Mehta with Akbar Padamsee, Jagdish Swaminathan and Ashok Vajpeyi, c. 1980s

Photograph of Tyeb and Sakina Mehta with Akbar Padamsee, Jagdish Swaminathan and Ashok Vajpeyi. Inscribed with names of the artist and the photographer on the reverse.

Pradbodh Parikh, Tyeb Mehta and Sakina Mehta, c.1980s

Photograph of Prabodh Parikh in conversation with Tyeb Mehta as Sakina Mehta listens on a terrace.

After his graduation, from JJ School, Tyeb looks after his family’s cinema business in Pune.

In 1954, he briefly visits Paris and London to study modern masters. He returns back to India after four months.

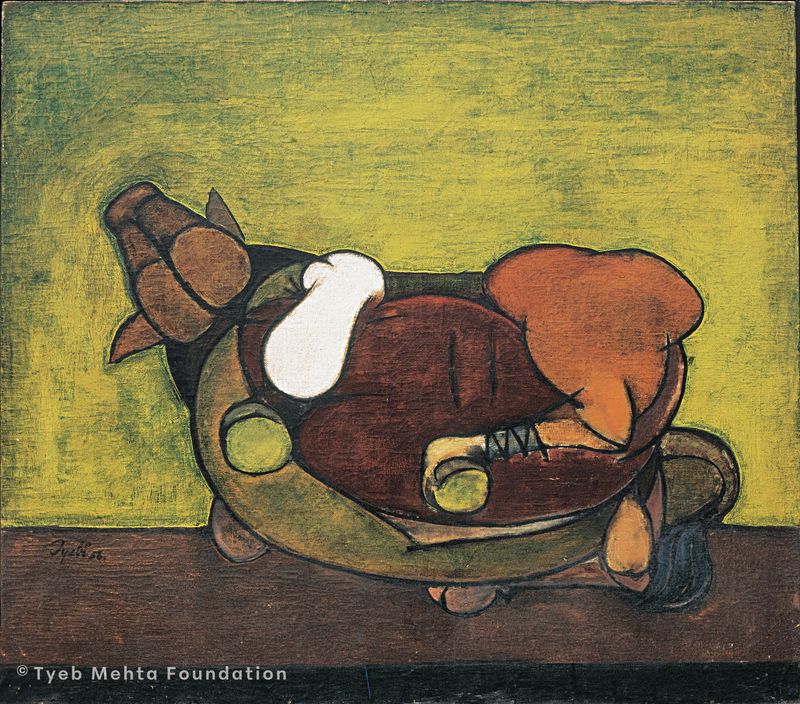

In 1956, Tyeb paints Trussed Bull, one of his major works and a repeating imagery in his practice.

In 1957, Tyeb joins the Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University of Baroda, but he could not continue beyond four months due to personal reasons.

At that time I lived in Mohammed Ali Road. You know the story. The crowds beat the man to death, smashed his head with stones. I was sick with fever for days afterwards and the image still haunts me. Even today I can’t bear the sight of blood. I was looking for an image to express this anguish and, years later, I found it in the British Museum. I was fascinated by the image of the trussed bull in the Egyptian bas-relief and created my first major painting, The Trussed Bull, in 1956.

As the discovery of an image, the trussed bull was important for me on several levels. As a statement of great energy… blocked or tied up. The way they tie up the animal’s legs and fling it on the floor of the slaughterhouse before butchering it… you feel something very vital has been lost. The trussed bull also seemed representative of the national condition… the mass of humanity unable to channel or direct its tremendous energies. Perhaps also my own feeling about my early life in a tightly knit, almost oppressive community…

— Tonalities: A Conversation with Tyeb Mehta, Nancy Adajania, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

Trussed Bull, 1956, 101.6×127 cm, oil on canvas

Figure with Trussed Bull, 1958, 60×90 cm, oil on canvas

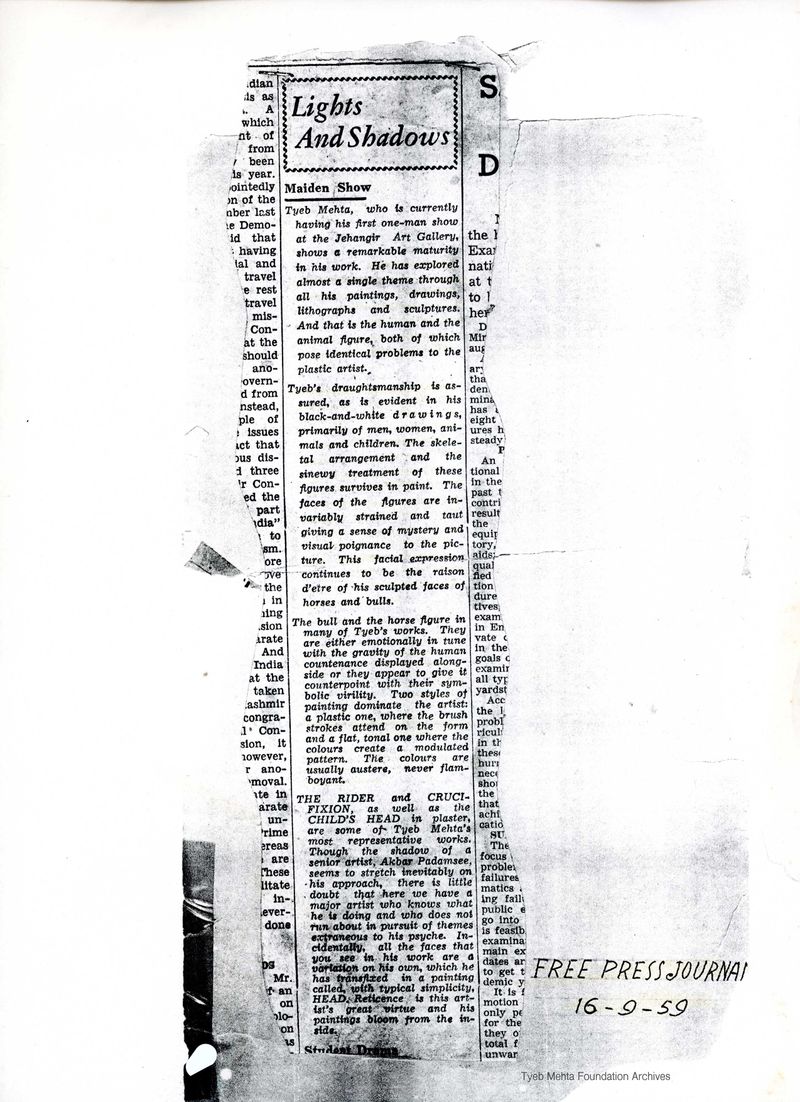

On 14th September 1959, the first show of Tyeb’s paintings opens at Gallery 59, organised by Bal Chhabda; Ebrahim Alkazi inaugurates the show.

Ebrahim Alkazi at Tyeb Mehta’s Exhibition, in 1959, Gallery 59

Photograph of capturing Ebrahim Alkazi delivering a speech at Tyeb Mehta’s exhibition organised by Gallery 59, Bombay, in 1959. The image also features Tyeb Mehta and Bal Chhabda.

Tyeb Mehta, 1959, Gallery 1959

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta as he stands looking at the display of his first solo exhibition in 1959, organised by Gallery 59, Bombay. Inscribed with year and location in pencil on the reverse.

Lights and Shadows

Press clipping of Tyeb Mehta’s solo exhibition at Jehangir Gallery, Bombay, in September 1959.

In 1960, with decent earnings from his first solo exhibition at gallery 59, Tyeb, with his wife and son, travels to London again, where he and his wife sustain themselves through various livelihood jobs.

In 1962, Tyeb exhibits his works at Bare Lane Gallery, Oxford, England.

Exhibiting widely during his time in London, he returns to Bombay in November, 1964, and settles in New Delhi in 1965.

In London, in the 1960s, my wife Sakina and I would visit the National Gallery in the lunch break and sit in front of the old masters, particularly Uccello and Piero della Francesca’s works. I was attracted to the Italian masters’ concern with form and more significantly their mathematical exactitude in composition and rendering of human figures. El Greco’s paintings with their elongated bodies were engaging as well.

— Tonalities: A Conversation with Tyeb Mehta, Nancy Adajania, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

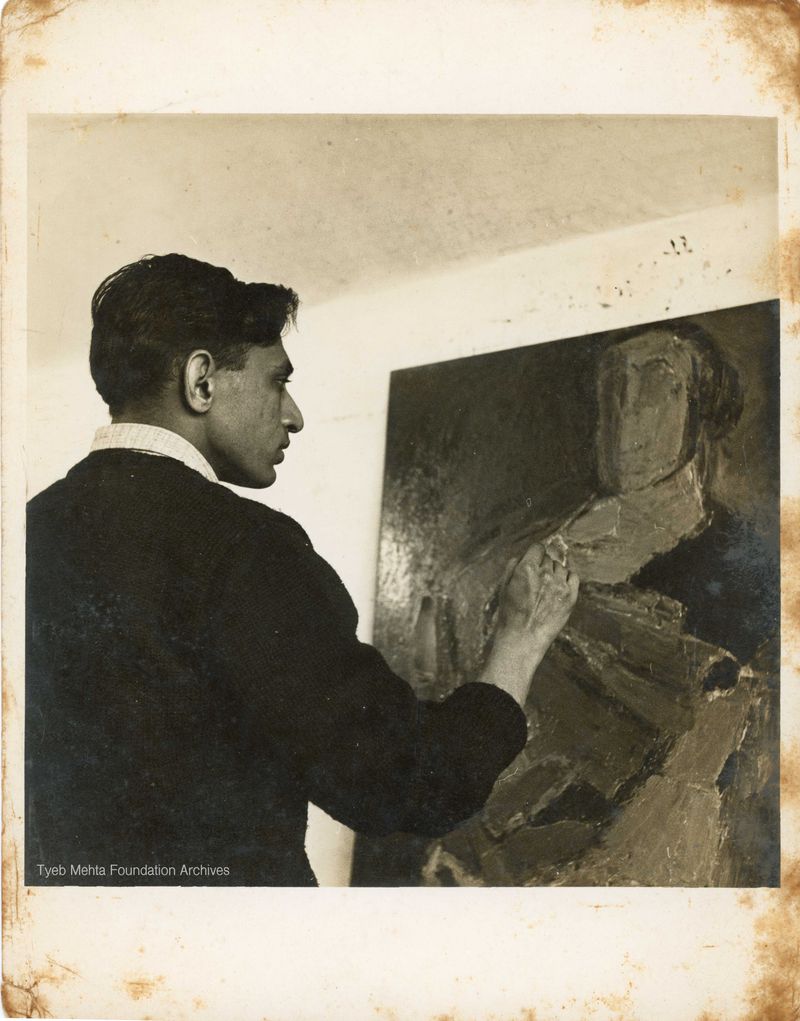

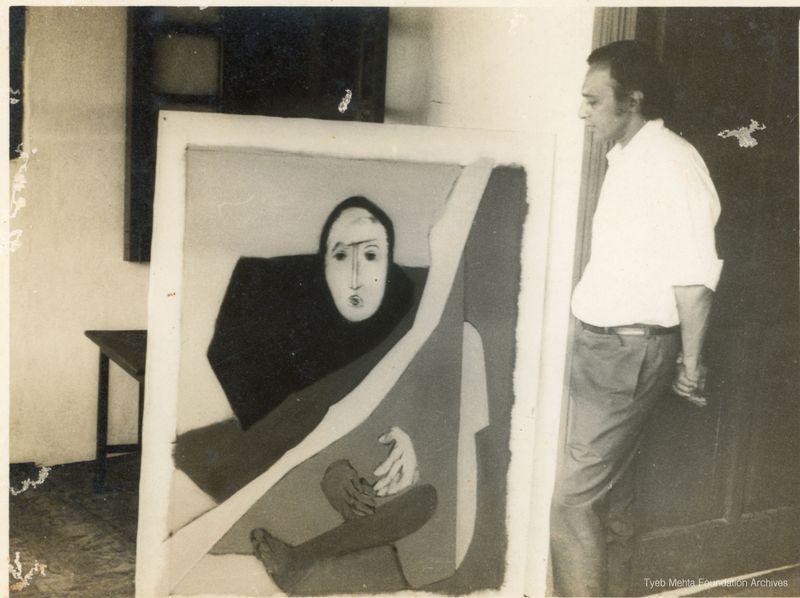

Tyeb Mehta with painting, c. 1960s

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta working on his painting.

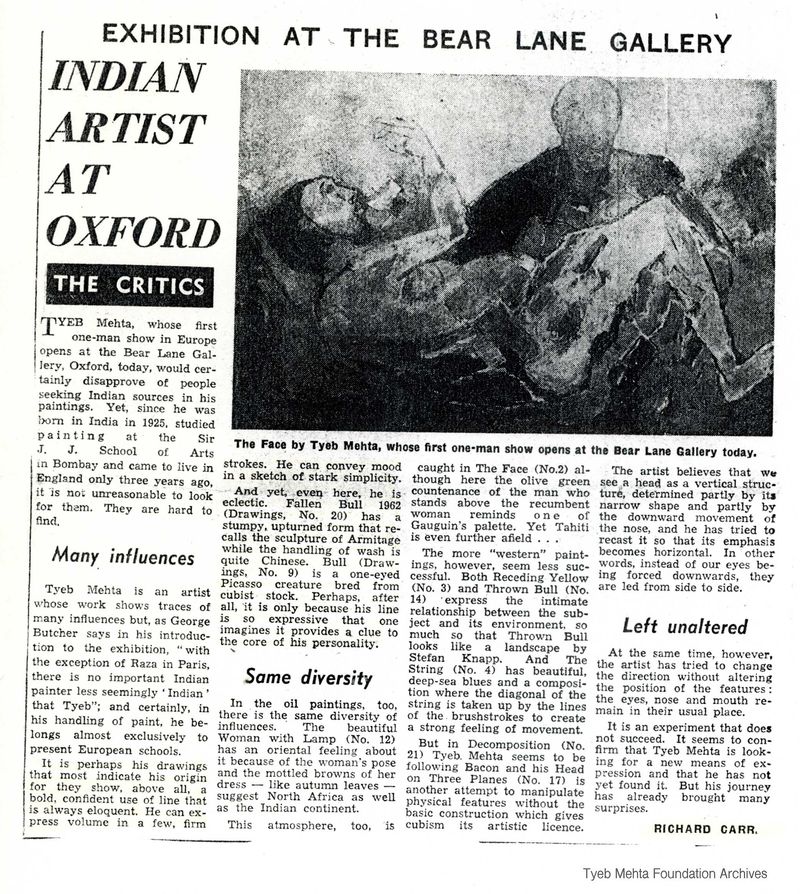

Indian Artist at Oxford

Press clipping of Tyeb Mehta’s solo exhibition at Bear Lane Gallery, Oxford, in 1962.

Two years later, in November 1961, with the British art critic George Butcher as its honorary curator, the Bare Lane Gallery, Oxford, England showed the work of 21 South Asian Artists… It was George Butcher, a respected English art critic, familiar with modern Indian artists and who did not hesitate to compare them with their Western contemporaries, proved a turning point in the early appreciation of Tyeb Mehta’s work.

— Celebrating Tyeb Mehta, Dilip Chitre, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

Nayika, 1962, 114×102 cm, oil on board

Figure, 1962, 102×96 cm, oil on canvas

Tyeb paints Falling Figure, yet another repeating and celebrated imagery from his lifelong oeuvre.

The motif of the falling figure observes a regular shift in formal execution—from the raw intensity of his expressionist phase to the measured precision of his later paintings—yet the underlying spirit and existential urgency of the theme remain unaltered.

Tyeb Mehta with M.C. Chagla

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta with Justice M.C. Chagla at Kumar Gallery, New Delhi, in 1966.

Tyeb exhibits the Falling Figure at the first triennale, Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi

Tyeb receives the Rockefeller 3rd Fund Fellowship to work and study in the US. In this year, he extensively travels in the US, visiting noted museums and viewing modern and contemporary master works.

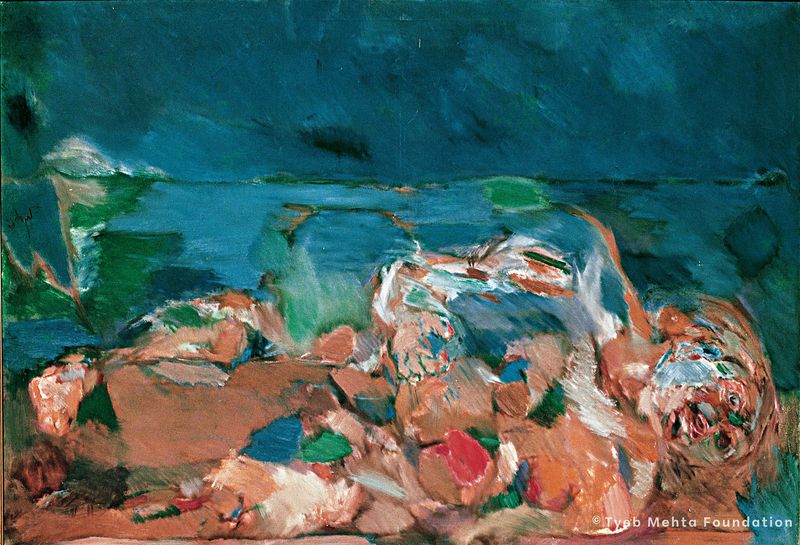

Reclining Figure, 1966-67, 122×183 cm, oil on canvas

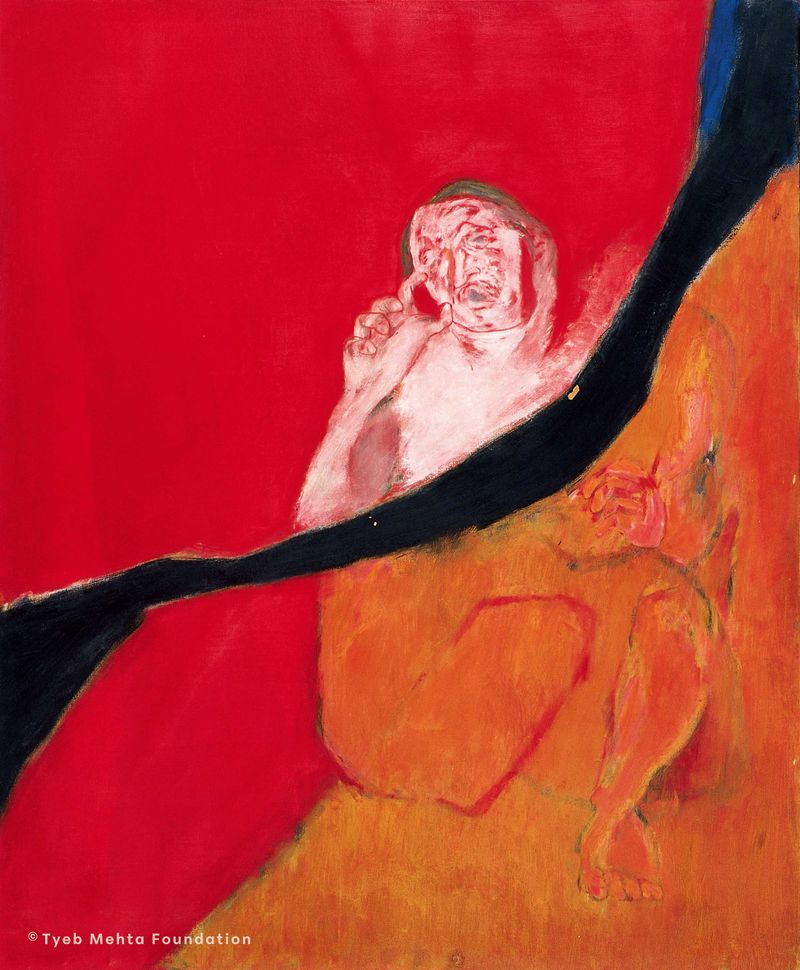

Tyeb inducts the diagonal element in his paintings, which he continues until 1976.

After returning from overseas and receiving a fresh experience of Minimalism with a sudden stage of impasse, Tyeb while painting decides to discard his work scratching off through paint, accidentally falling upon an inquisitive moment of diagonal, which realises a new sense of planes in relooking at figures.

NS: Throughout the seventies, a diagonal element dominated your work and in conjunction with your ‘falling figure’, became almost a hallmark. What gave rise to the diagonal?

TM: I was trying to work out a way to define space… to activate a canvas. If I divided it horizontally and vertically, I merely created a preponderance of smaller squares or rectangles. But if I cut the canvas with a diagonal, I immediately created a certain dislocation. I was able to distribute and divide a figure within the two created triangles and automatically disjoint and fragment it. Yet the diagonal maintained an almost centrifugal unity… in fact became a pictorial element in itself.

— Tonalities: A Conversation with Tyeb Mehta, Nancy Adajania, published in “Ideas, Images, Exchanges”, by Vadehra Art Gallery 2005.

Tyeb Mehta standing by Diagonal series, c. 1960s - 1970s

Photograph of Tyeb Mehta standing by a canvas of a painting from his ‘Diagonal’ series.

This slashing weapon demands to be contextualised in more historically specific ways. As the archetypal sign of scission, the diagonal is the most prominent expression of the psychology of the schism that has haunted Tyeb: since it emphasises separation and twinning in the same gesture, it proposes a doubling of consciousness and an awareness of difference-within-belonging at various levels, whether indicating the minority braced within the majority, or the artist within a larger public. There has been, in Tyeb’s art practice, the constant sense of playing a double life: between cultural identities, between life choices. As I hope to show in the course of this monograph, it is as though Tyeb has always wished, simultaneously, to maintain and defy a secrecy of meaning. Thus, the diagonal becomes a metaphor for Tyeb’s world-view, encoding as it does the two principal impulses that inform his poetics: the first, towards survival, leading to silence, abstraction, the burial of clues; the other, equally urgent and insistent, towards articulation, leading to the soundless but unmistakable voice, figuration, the image.

— Ranjit Hoskote, Images of Transcendence, Towards a New Reading of Tyeb Mehta’s Art, Ideas Images, Exchanges

Diagonal, 1969, 150 × 125 cm, oil on canvas

Diagonal, 1973, 176×260 cm, oil on canvas

Diagonal, 1974, 175×120 cm, oil on canvas

India

In the 1960s and 70s, Indian modernists such as Akbar Padamsee, V. S. Gaitonde, Ram Kumar, and Krishen Khanna received the Rockefeller III Fund Fellowship, which enabled them to travel and work in the United States. Through this support, they engaged directly with postwar American art—Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimalism—broadening their vocabularies and positioning Indian modernism within an increasingly global cultural dialogue

The 1980s in Indian art witnessed a a departing duration from the formal and modernist fervour of earlier decades. Artists began emphasising narrative figuration, and socially as well as political charged works that highlighted socio-economic realities, communal tensions, and the rise of identity politics through artists like Bhupen Khakhar, Gulammohammed Sheikh, and Nalini Malani. This decade laid the foundation for contemporary Indian art by opening discourse to public art voices, regional traditions and political engagement.

Global

The 1970s were a decade of radical questioning in global art — politically charged, conceptually rigorous, and socially conscious. If the 1960s exploded the boundaries of what art could be, the 1970s deepened that inquiry: artists turned toward ideas, activism, identity, and process rather than objects or beauty.

The 1970s marked a shift from object-based modernism to idea-based and socially engaged postmodernism. It was an era of conceptual clarity, feminist assertion, body politics, ecological awareness, and institutional critique.

Through waves of institutional critique in 1980, artists and scholars pushed the definitions of Art, steering their inquiries into social concerns, augmenting a change with the institutions and positions.

The genres of body or performance art, video art, installations and new media art become concretised and mobile mediums of expressing the live concerns of the world. The human condition found a voice through these live presentation.